Oh, my, will you look at them leaves a-flying. And how nice it is to be up here, setting on your porch, even if we have to holler at one another from a safe distance. This old covid thing has kept me right close to home and it's a pleasure to be here looking off in the faraway; a body needs to rest her eyes on the faraway now and then, don't you think? That's why I asked could we visit a spell up here after I made the rounds of my folks in the graveyard.

I didn't hardly know what to think when you come riding across my bridge in that little open vehicle of yours. I'd made up my mind I couldn't go visiting the Quiet Ones this Halloween, being as I ain't up to the walk and Dor'thy is just now getting better --law, she had a close call with that covid like quite a few others in her church. I don't hold with expecting the Lord to do all that work--seems like if he gave us common sense and doctors and them maskes, we had ought to use them.

But you hustled me off in that little whatamacallit and we cadillaced in the open air right up that steep road. I got to do my visiting and leave my bits of spice cake--for I'd made the cake, just out of habit, I reckon. Get you another piece and I'll tell you about that gravestone you was asking about, the one for George Washington Gentry.

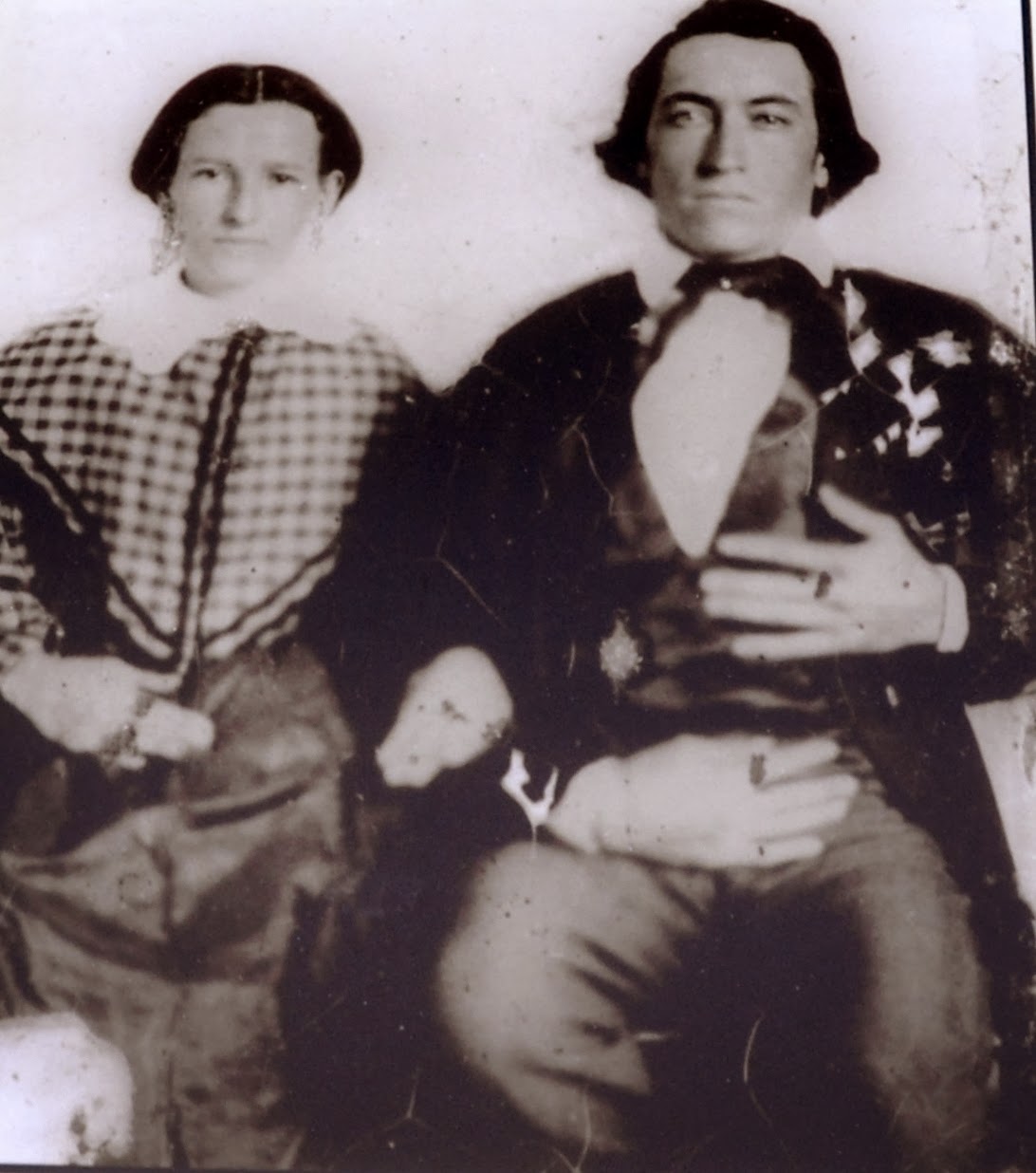

I know you was puzzling over what it said about old Wash, (for that was what everyone called him, according to Luther who was his great, great grandson.) It showed G.W. Gentry was a member of a Confederate regiment and a Union cavalry troop. Even had both flags there, crossed together.

Now from what folks has said, the only thing uncommon about that is that Wash claimed both sides. There was a many in this part of the world didn't want no part of that fight but was conscripted if they couldn't pay to send another in their place. And many of them deserted then joined on the Union side for fear of being shot as a deserter if they was found at home.

But that weren't the case with Wash. Now, the way Luther told it, Wash weren't much more than a boy when he run off and joined up with the Confederates. He was tired of farm work and his old daddy was rough as a cob and bad to whip any young un that didn't do just so. And Wash was full of notions about soldiering and wearing a fancy uniform and marching behind a band. From the few letters he wrote home, they could tell he was disappointed that the part of the army he was with didn't have no great battles to speak of but did guard duty and such here and there.

And then when they was in winter camp for the longest time, the bloody flux took hold till most of the men spent all their time at the latrines, that is, could they get there. Wash was one of the worst took of all and when the officers decided to move camp to get away from them overflowing latrines, Wash got loaded onto a wagon with some of the others what couldn't walk. They was packed in tight, with some partly overlaying the others and you can just imagine how nasty it was for them pore fellers being as how they didn't have control of their bowels.

Anyways, the wagon bumped along and Wash was in such bad case that he passed out and only come to when there weren't no more bumping and jolting. It was black night but as the moon rose--and it was a full moon, like we'll have tonight, he could see that the wagon was all by itself--mules and driver gone and the others around him not moving a lick.

Wash thought this must be some kind of bad dream, but the dreadful smell was real enough. He managed to pull himself out from under the feller next to him and as he did, he realized that feller was a corpse, stiff and cold. As he felt around, it soon became clear they was all corpses, 'cepting him, and he began not to be so sure about hisself.

"Oh, Lord," says Wash, "what shall I do?"

Well, weak though he was, he managed to get hisself off of that wagonload of dead men and to lay down against the bank at the side of the road. He could see now that one of the wagon wheels was plumb busted to pieces and he began to hope that maybe the driver would come back with the mules and another wheel. It didn't seem like they'd leave all them fellers unburied.

Just then Wash saw a light come bobbling along down the road, from the direction the wagon had been heading. He tried to stand up but all that he could do was to wave one arm and croak out a pitiful Help!

The light kept on a-coming and afore long, Wash saw it was a pack peddler, leading a mule. "Over here," called Wash, "I'm in sore need of a helping hand."

The peddler stopped, then lifted his lantern high. "The soldiers told me I'd find a wagon of corpses down this way. They didn't mention you. You're no corpse, I see."

"That I ain't, though I reckon they thought I was," said Wash. "I'd take it kindly was you to give me some water--I think if I had a drink, I might be able to stand."

The peddler brought over a canteen, then when Wash had taken a good sup, pulled out a flask. "Cherry brandy, from Gudger's Stand. It's near strong enough to raise the dead."

When Wash had taken a pull or two from that flask, he was able to push hisself off the ground. He was standing there, swaying and wondering what he had ought to do next when the peddler said, "They aren't coming back for you, my friend. The officer in charge was in a tearing hurry to get his troops to some certain place by morning. And they believe you to be dead." The peddler stroked his long black beard and looked Wash up and down. "What you have now is a chance to make a change in your life's direction."

Wash studied on it. He'd tried to be a good soldier for the South, even while others was deserting. And now, looked like the South had deserted him.

The peddler went on talking, saying he could put Wash on his mule and carry him to some folks he knew who'd take him in and care for him till he was stronger. "And then you can make your decision."

Well, that's what happened. The peddler helped Wash onto the mule and they ambled on till long about daybreak, they come to a pretty little cabin in a clearing. There was smoke rising from the chimbley and the smell of cornbread in the air. Just then a girl come out the door and called to the chickens what was roosting on the ridgepole. She flung out a few handfuls of corn and them old biddies come a-running. The peddler stopped and called out 'Hello, the house."

The girl looked up and smiled big. "Why, hello yourself, Jacob! Come in and get you some breakfast."

Wash always said that he fell in love with her right then. But what happened was that he clumb down and kindly hid behind the mule, so ashamed of his nasty clothes that he didn't want to come near to that pretty girl. He whispered as much to the peddler who spoke to the girl and then led Wash over to the branch what run near the house. Wash stripped off his dirty shirt and britches and doused hisself good in that cold water. The peddler even give him a bit of soap and had a clean pair af britches and a homespun shirt waiting for Wash to put on.

"Hit was better than any baptizing," Wash would tell folks forever after. "I put off the old Wash and aimed to find the new one."

Law, honey, is that the moon beginning to rise? I need to finish up this story so's you can run me home. Though I reckon you can guess the rest. The peddler left him there and the folks took good care of him. The girl's brothers was all with the Union Army and when they came home on leave, they took Wash back with them to join up on their side. The war was near over and he never saw even the least bit of shooting. When he was let go, him and the brothers rode back and Wash married that pretty girl. And they named their first youngun Aaron, after the peddler. That was Luther's great granddaddy."

The old woman watches the rising moon, her eyes gazing into the distance. . . and the past . . .

"I one time knowed a peddler named Aaron. He give me a candy stick when I was a little girl. And I think it was the same feller helped me out of a tight spot some years later. And then, not too far back of this. I thought I saw him again . . . but likely my rememberer ain't working just right. Still, he was a fine somebody, that Mr. Aaron. Wonder iffen he was kin to Wash's peddler?

There go more of them leaves, hurrying down to the ground. Just like folks, I sometime think, and sometimes I give a name to each leaf. So many that I've knowed . . .There goes Old Wash and Luther and Cletus and my angels, all gone before me. And me still hanging on, withered up right much, but enjoying the view.